Finally! There is a movement to make education research more relevant to educators and edtech providers alike.

At various conferences, we’ve been hearing about a rebellion against the “business as usual” of research, which fails to answer the question of, “Will this product work in this particular school or community?” For educators, the motive is to find edtech products that best serve their students’ unique needs. For edtech vendors, it’s an issue of whether research can be cost-effective, while still identifying a product’s impact, as well as helping to maximize product/market fit.

The “business as usual” approach against which folks are rebelling is that of the U.S. Education Department (ED). We’ll call it the regime. As established by the Education Sciences Reform Act of 2002 and the Institute of Education Sciences (IES), the regime anointed the randomized control trial (or RCT) as the gold standard for demonstrating that a product, program, or policy caused an outcome.

Let us illustrate two ways in which the regime fails edtech stakeholders.

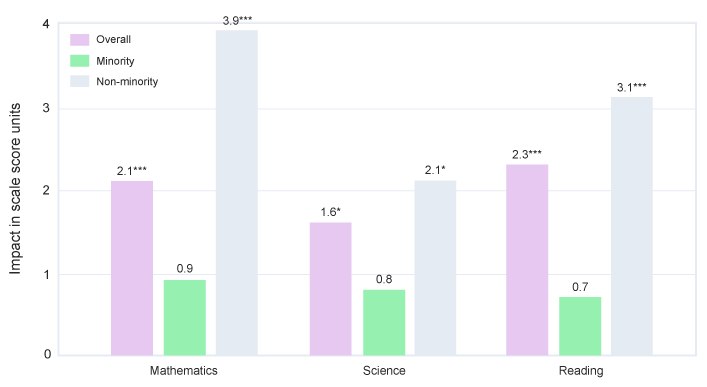

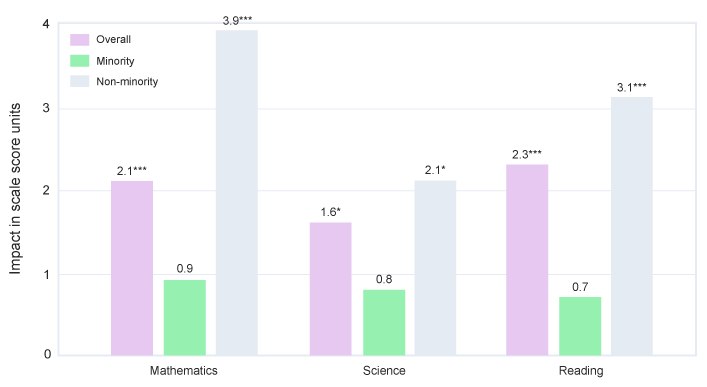

First, the regime is concerned with the purity of the research design, but not whether a product is a good fit for a school given its population, resources, etc. For example, in an 80-school RCT that the Empirical team conducted under an IES contract on a statewide STEM program, we were required to report the average effect, which showed a small but significant improvement in math scores (Newman et al., 2012). The table on page 104 of the report shows that while the program improved math scores on average across all students, it didn’t improve math scores for minority students. The graph that we provide here illustrates the numbers from the table and was presented later at a research conference.

IES had reasons couched in experimental design for downplaying anything but the primary, average finding, however this ignores the needs of educators with large minority student populations, as well as of edtech vendors that wish to better serve minority communities.

Our RCT was also expensive and took many years, which illustrates the second failing of the regime: conventional research is too slow for the fast-moving innovative edtech development cycles, as well as too expensive to conduct enough research to address the thousands of products out there.

These issues of irrelevance and impracticality were highlighted last year in an “academic symposium” of 275 researchers, edtech innovators, funders, and others convened by the organization now called Jefferson Education Exchange (JEX). A popular rallying cry coming out of the symposium is to eschew the regime’s brand of research and begin collecting product reviews from front-line educators. This would become a Consumer Reports for edtech. Factors associated with differences in implementation are cited as a major target for data collection. Bart Epstein, JEX’s CEO, points out: “Variability among and between school cultures, priorities, preferences, professional development, and technical factors tend to affect the outcomes associated with education technology. A district leader once put it to me this way: ‘a bad intervention implemented well can produce far better outcomes than a good intervention implemented poorly’.”

Here’s why the Consumer Reports idea won’t work. Good implementation of a program can translate into gains on outcomes of interest, such as improved achievement, reduction in discipline referrals, and retention of staff, but only if the program is effective. Evidence that the product caused a gain on the outcome of interest is needed or else all you measure is the ease of implementation and student engagement. You wouldn’t know if the teachers and students were wasting their time with a product that doesn’t work.

We at Empirical Education are joining the rebellion. The guidelines for research on edtech products we recently prepared for the industry and made available here is a step toward showing an alternative to the regime while adopting important advances in the Every Student Succeeds Act (ESSA).

We share the basic concern that established ways of conducting research do not answer the basic question that educators and edtech providers have: “Is this product likely to work in this school?” But we have a different way of understanding the problem. From years of working on federal contracts (often as a small business subcontractor), we understand that ED cannot afford to oversee a large number of small contracts. When there is a policy or program to evaluate, they find it necessary to put out multi-million-dollar, multi-year contracts. These large contracts suit university researchers, who are not in a rush, and large research companies that have adjusted their overhead rates and staffing to perform on these contracts. As a consequence, the regime becomes focused on the perfection in the design, conduct, and reporting of the single study that is intended to give the product, program, or policy a thumbs-up or thumbs-down.

There’s still a need for a causal research design that can link conditions such as resources, demographics, or teacher effectiveness with educational outcomes of interest. In research terminology, these conditions are called “moderators,” and in most causal study designs, their impact can be measured.

The rebellion should be driving an increase the number of studies by lowering their cost and turn-around time. Given our recent experience with studies of edtech products, this reduction can reach a factor of 100. Instead of one study that costs $3 million and takes 5 years, think in terms of a hundred studies that cost $30,000 each and are completed in less than a month. If for each product, there are 5 to 10 studies that are combined, they would provide enough variation and numbers of students and schools to detect differences in kinds of schools, kinds of students, and patterns of implementation so as to find where it works best. As each new study is added, our understanding of how it works and with whom improves.

It won’t be enough to have reviews of product implementation. We need an independent measure of whether—when implemented well—the intervention is capable of a positive outcome. We need to know that it can make (i.e., cause) a difference AND under what conditions. We don’t want to throw out research designs that can detect and measure effect sizes, but we should stop paying for studies that are slow and expensive.

Our guidelines for edtech research detail multiple ways that edtech providers can adapt research to better work for them, especially in the era of ESSA. Many of the key recommendations are consistent with the goals of the rebellion:

- The usage data collected by edtech products from students and teachers gives researchers very precise information on how well the program was implemented in each school and class. It identifies the schools and classes where implementation met the threshold for which the product was designed. This is a key to lowering cost and turn-around time.

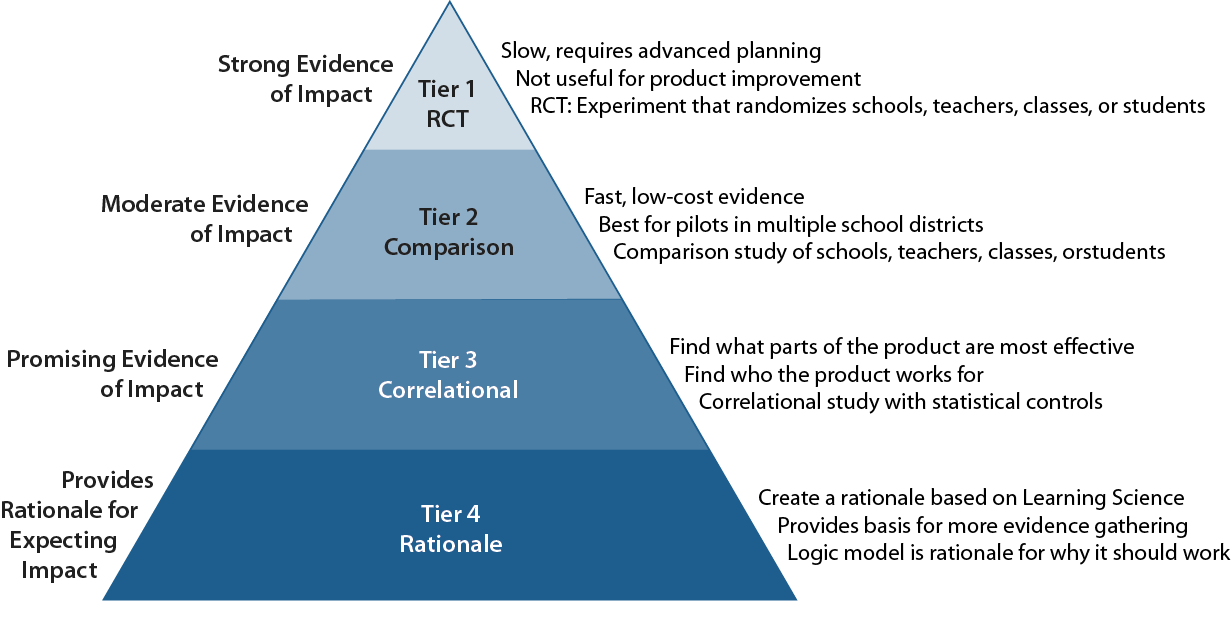

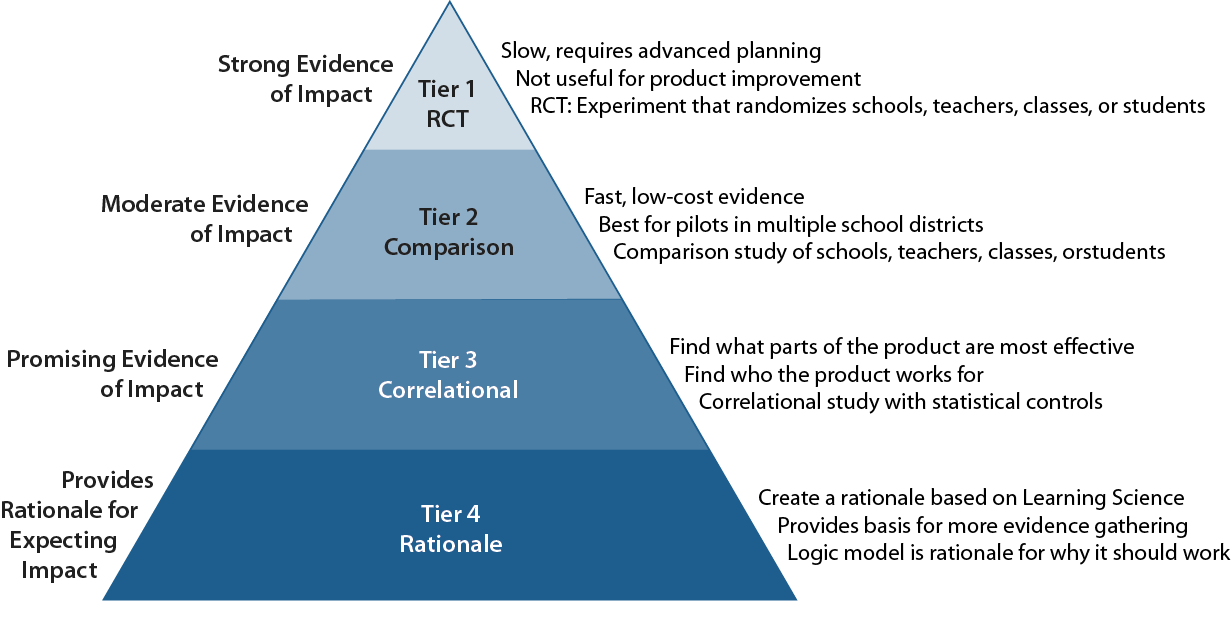

- ESSA offers four levels of evidence which form a developmental sequence, where the base level is based on existing learning science and provides a rationale for why a school should try it. The next level looks for a correlation between an important element in the rationale (measured through usage of that part of the product) and a relevant outcome. This is accepted by ESSA as evidence of promise, informs the developers how the product works, and helps product marketing teams get the right fit to the market.

- The ESSA level that provides moderate evidence that the product caused the observed impact requires a comparison group matched to the students or schools that were identified as the users. The regime requires researchers to report only the difference between the user and comparison groups on average. Our guidelines insist that researchers must also estimate the extent to which an intervention is differentially effective for different demographic categories or implementation conditions.

From the point of view of the regime, nothing in these guidelines actually breaks the rules and regulations of ESSA’s evidence standards. Educators, developers, and researchers should feel empowered to collect data on implementation, calculate subgroup impacts, and use their own data to generate evidence sufficient for their own decisions.

A version of this article was published in the Edmarket Essentials magazine.