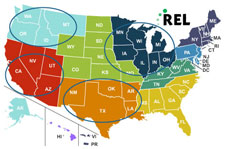

Two New Studies for Regional Education Laboratory (REL) Southwest Completed

Student Group Differences in Arkansas Indicators of Postsecondary Readiness and Success

It is well documented that students from historically excluded communities face more challenges in school. They are often less likely to obtain postsecondary education, and as a result see less upward social mobility. Educational researchers and practitioners have developed policies aimed at disrupting this cycle. However, an important factor necessary to make these policies work is the ability of school administrators to identify students that are at risk of not reaching certain academic benchmarks and/or exhibit certain behavioral patterns that are correlated with future postsecondary success.

Arkansas Department of Education (ADE), like education authorities in many other states, is tracking K-12 students’ college readiness and enrollment and collecting a wide array of student progress indicators meant to predict their postsecondary success. A recent study by Regional Education Laboratory (REL) Southwest showed that a logistic regression model that uses a fairly small number of such indicators, measured as early as in seventh or eighth grade, predicts with a high degree of accuracy whether students will enroll in college four or five years later (Hester et al., 2021). But does this predictive model – and the entire “early warning” system that could rely on it – work equally well for all student groups? In general, predictive models are designed to reduce average prediction error. So, when the dataset used for predictive modeling covers several substantially different populations, the models tend to make more accurate predictions for the largest subset and less accurate for the rest of the observations. Meaning, if the sample your model relies on is mostly White, it will most accurately predict outcomes for White students. In addition, predictive strength of some indicators may vary across student groups. In practice, this means that such a model may turn out to be less useful to forecast the outcome for those students who should benefit the most from it

Researchers from Empirical Education and AIR teamed up to complete a study for REL Southwest that focuses on the differences in predictive strength and model accuracy across student groups. It was a massive analytical undertaking based on nine years of tracking two cohorts of six graders from the whole state, close to 80,000 records and hundreds of variables including student characteristics (including gender, race/ethnicity, eligibility for the National School Lunch Program, English learner student status, disability status, age, and district locale), middle and high school academic and behavioral indicators, and their interactions. First, we found that several student groups—including Black and Hispanic students, students eligible for the National School Lunch Program, English learner students, and students with disabilities—were substantially less likely (by 10 percentage points or more) to be ready for or enroll in college than students without these characteristics. However, our main finding, and a reassuring one, is that the model’s predictive power and predictive strength of most indicators is similar across student groups. In fact, the model often does a better job predicting postsecondary outcomes for those student groups in most need of support.

Let’s talk about what “better” means in a study like that. It is fair to say that statistical model quality is seldom of particular interest in educational research and is often limited to a footnote showing the value of R2 (the proportion of variation in the outcome explained by independent variables). It can tell us something about the amount of “noise” in the data, but it is hardly something that policy makers are normally concerned with. In the situation where the model’s ability to predict a binary outcome—whether or not the student went to college—is the primary concern, there is a clear need for an easily interpretable and actionable metric. We just need to know how often the model is likely to predict the future correctly based on current data.

Logistic regression, which is used for predicting binary outcomes, produces probabilities of outcomes. When the predicted probability (like that of college enrollment) is above fifty percent, then we say that it predicts success (“yes, this student will enroll”), and it predicts failure (“no, they will not enroll”) otherwise. When the actual outcomes are known, we can evaluate the accuracy of the model. Counting the cases in which the predicted outcome coincides with the actual one and dividing it by the total number of cases yields the overall model accuracy. The model accuracy is a useful metric that is typically reported in predictive studies with binary outcomes. We found, for example, that the model accuracy in predicting college persistence (students completing at least two years of college) is 70% when only middle school indicators are used as predictors, and it goes up to 75% when high school indicators are included. These statistics vary little across student groups, by no more than one or two percentage points. Although it is useful to know that outcomes two years after graduation from high school can be predicted with a decent accuracy in as early as eighth grade, the ultimate goal is to ensure that students at risk of failure are identified while schools still can provide them with necessary support. Unfortunately, such a metric as the model accuracy is not particularly helpful in this case.

Instead, a metric called “model specificity” in the parlance of predictive analytics lets us view the data from a different angle. It is calculated as a proportion of correctly predicted negative outcomes alone, ignoring the positive ones. The model specificity metric turns out to vary across student groups a lot in our study but the nature of this variation validates the ADE’s system: for the student groups in most need of support, the model specificity is higher than for the rest of the data. For some student groups, the model can detect that a student is not on track to postsecondary success with near certainty. For example, failure to attain college persistence is correctly predicted from middle school data in 91 percent of cases for English learner students compared to 65 percent for non-English learner students. Adding high school data into the mix lowers the gap—to 88 vs 76 percent—but specificity is still higher for the English learner students, and this pattern holds across all other student groups.

The predictive model used in the ADE study can certainly power an efficient early warning system. However, we need to keep in mind what those numbers mean. For some students from historically excluded communities, their early life experiences create significant obstacles down the road. Some high schools are not doing enough to put these students on a new track that would ensure college enrollment and graduation. It is also worth noting that while this study provides evidence that ADE has developed an effective system of indicators, the observations used in the study come from the two cohorts of students who were in the sixth graders in 2008–09 and 2009–10. Many socioeconomic conditions have changed since then. Thus, the only way to assure that the models remain accurate is to proceed from isolated studies to building “live” predictive tools that would update the models as soon as a new annual batch of outcome data becomes available.

Read complete report titled “Student Group Differences In Arkansas’ Indicators of Postsecondary Readiness and Success” here.

Early Progress and Outcomes of a Grow Your Own Grant Program for High School Students and Paraprofessionals in Texas

Shortage and high turnover of teachers is a problem that rural schools face across the nation. Empirical Education researchers have contributed to the search for solutions for this problem several times in recent years, including two studies completed for REL Southwest (Sullivan, et al., 2017; Lazarev et al., 2017). While much of the policy research is focused on the ways to recruit and retain credentialed teachers, some states are exploring novel methods to create new pathways into the profession that would help create new local teacher cadres. One such promising initiative is Grow Your Own (GYO) program funded by the Texas Education Agency (TEA). Starting in 2019, TEA provides grants to schools and districts that intend to expand the local teacher labor force through one or both of the following pathways. The first pathway offers high school students an early start in teacher preparation through a sequence of education and training courses. The second pathway aims to help paraprofessionals already employed by schools to transition into teaching positions by covering tuition for credentialing programs, as well as offering a stipend for living expenses.

In the joint project with AIR, Empirical Education researchers explored the potential of the first pathway for high school students to address teacher shortages in rural communities and to increase the diversity of teachers. Since this is a new program, our study was based on the first two years of implementation. We found promising evidence that GYO can positively impact rural communities and increase teacher diversity. For example, GYO grants were allocated primarily to rural and small town communities, and programs were implemented in smaller schools with a higher percentage of Hispanic students and economically disadvantaged students. Participating schools also had higher enrollment in the teacher preparation courses. In short, GYO seems to be reaching rural areas with smaller and more diverse schools, and is boosting enrollment in teacher preparation courses in these areas. However, we also found that fewer than 10% of students in participating districts completed at least one education and training course, and fewer than 1% of students completed the full sequence of courses. Additionally, white and female students are overrepresented in these courses. These and other preliminary results will help the state education agency to fine-tune the program and work toward a successful final result: a greater number and increased diversity of effective teachers who are from the community in which they teach. We look forward to continuing research on the impact of “Grow Your Own.”

Read complete report titled “Early Progress and Outcomes of a Grow Your Own Grant Program for High School Students and Paraprofessionals in Texas” here.

All research Empirical Education has conducted for REL Southwest can be found on our REL-SW webpage.

References

Hester, C., Plank, S., Cotla, C., Bailey, P., & Gerdeman, D. (2021). Identifying Indicators That Predict Postsecondary Readiness and Success in Arkansas. REL 2021-091. Regional Educational Laboratory Southwest. https://eric.ed.gov/?id=ED613040

Lazarev, V., Toby, M., Zacamy, J., Lin L., & Newman, D. (2017). Indicators of Successful Teacher Recruitment and Retention in Oklahoma Rural Schools (REL 2018–275). U.S. Department of Education, Institute of Education Sciences, National Center for Education Evaluation and Regional Assistance, Regional Educational Laboratory Southwest. https://ies.ed.gov/ncee/rel/Products/Publication/3872.

Sullivan, K., Barkowski, E., Lindsay, J., Lazarev, V., Nguyen, T., Newman, D., & Lin, L. (2017). Trends in Teacher Mobility in Texas and Associations with Teacher, Student, and School Characteristics (REL 2018–283). U.S. Department of Education, Institute of Education Sciences, National Center for Education Evaluation and Regional Assistance, Regional Educational Laboratory Southwest. https://ies.ed.gov/ncee/rel/Products/Publication/3883