In December 2022, Rock Island-Milan School District #41 (RIMSD), in partnership with the Connect with Kids Network (CWK) and Empirical Education Inc., received an Early-Phase Education Innovation and Research (EIR) grant from the U.S. Department of Education to develop, implement, and evaluate How Are the Children (HATC), a high-school level social-emotional learning (SEL) curriculum.

“And how are the children?” is the traditional greeting of Maasai tribe warriors. The expression suggests that the true strength of a community is determined by the well-being of its children. Inspired by this idea, CWK developed the HATC curriculum. HATC is an SEL curriculum that uses project-based learning modules to engage students in learning through the lens of documentary filmmaking. The HATC curriculum includes lessons built around the five SE competencies identified by The Collaborative for Academic, Social, and Emotional Learning (CASEL): self-awareness, self-management, responsible decision-making, social awareness, and relationship skills.

HATC was implemented in two high schools in RIMSD, Rock Island High School (RIHS) and Thurgood Marshall Learning Center (TMLC). Rock Island, Illinois is a small, suburban city located approximately 175 miles west of Chicago. RIHS or "Rocky" as it is known to its students, is a four-year public high school. In the 2023–24 school year, RIHS served approximately 1,700 students in grades 9–12. Each day at RIHS is made up of seven class periods, including a 25-minute advisory period during which HATC was implemented. TMLC is the referral school for RIMSD, and serves approximately 100 students in grades 7–12 in an alternative school setting. TMLC serves students with a variety of academic and social needs. TMLC offers a more flexible learning environment, with more one-on-one interaction with educators, and curriculum resources designed to support and meet the specific needs of the students being served. Each day at TMLC is made up of four 90-minute periods.

This report presents findings from a one-year teacher-level randomized control trial (RCT) evaluating HATC. The study assessed HATC’s implementation fidelity, and its impacts on teachers and students at RIHS and TMLC during the 2023–2024 school year. For this experimental study, recruitment occurred at two timepoints. In spring 2023, we worked with RIMSD to recruit 44 teachers from RIHS who would lead an advisory class during the 2023–24 school year. After collecting baseline data from teachers and about their students, we randomly assigned 44 RIHS teachers into two groups: a group of teachers to be trained on and use HATC (i.e., the HATC group) and a group of teachers to continue with their existing advisory class (i.e., the control group or the business as usual (BAU) group). In fall 2023, we worked with RIMSD to recruit nine 9th–12th grade teachers from TMLC. As with the RIHS teachers, the nine TMLC teachers were randomly assigned into two groups: HATC or BAU. TMLC teachers implemented HATC during a 20-25 minute portion of their second block class. Data for the study were collected via teacher surveys and interviews. Student administrative data was provided by RIMSD, including student demographics, behavioral and academic outcomes, and student SE competencies, as measured by the DESSA-High School Edition (DESSA-HSE). (Notably, class rosters were determined before randomization, and attrition of teachers and students was low enough that the study could meet What Works Clearinghouse Evidence Standards without reservation.)

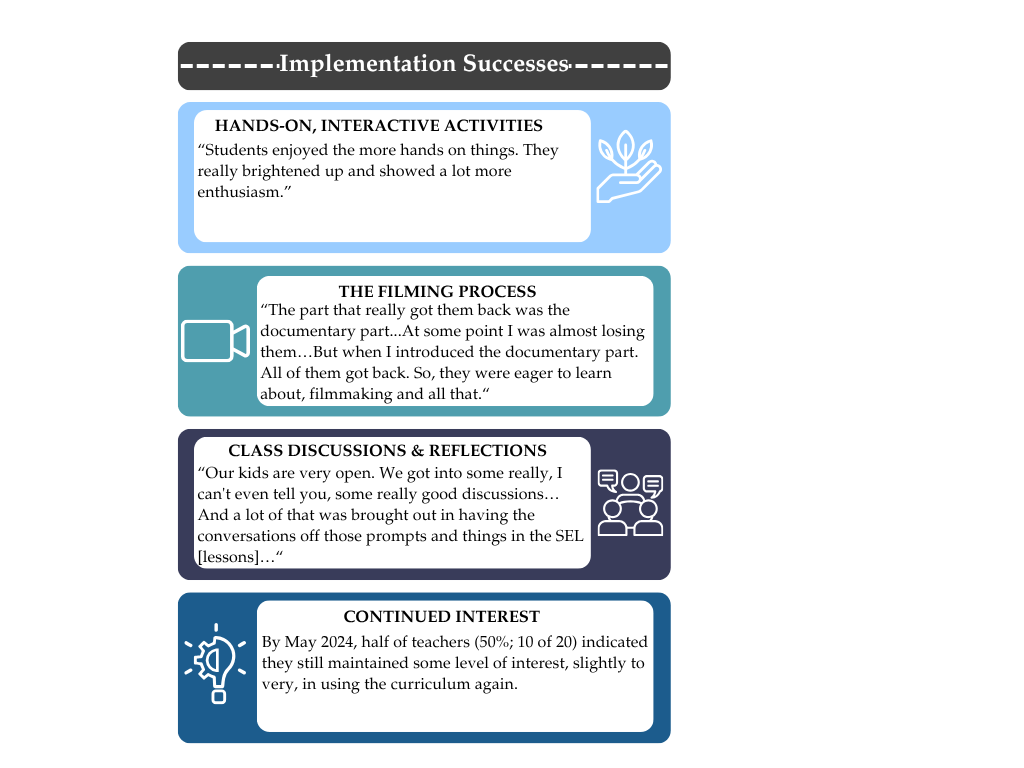

On each survey and in teacher interviews, we asked teachers to identify what was going well in their implementation. We consolidated responses across surveys and interviews to create a description of the key themes that emerged.

Overall, for the teachers able to maintain student engagement, HATC appeared to be an exciting opportunity for students that brought classrooms together and left students with a feeling of pride.

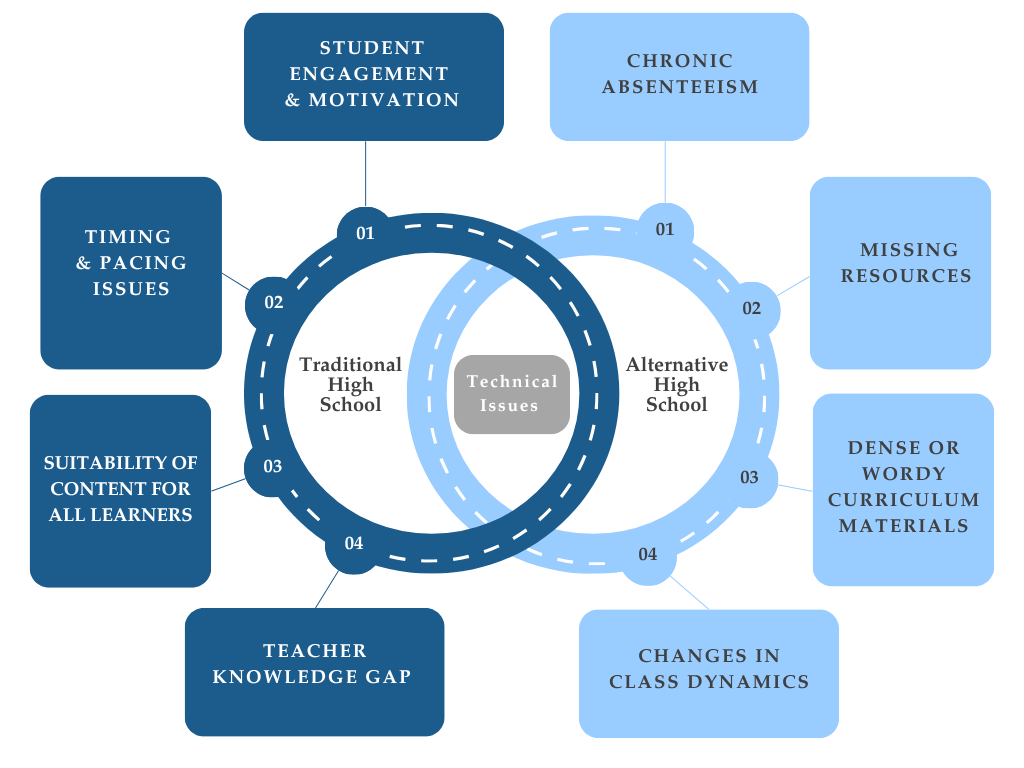

On each teacher survey and in teacher interviews, we asked teachers to identify any difficulties they experienced while implementing the curriculum. We consolidated responses across surveys and interviews to create a description of key themes that emerged. Upon reviewing responses, it became clear that RIHS and TMLC have important structural differences, which contributed to differences in their implementation experiences. Based on these considerations, we present key themes separately for each school.

We did not observe any impacts of HATC on teacher outcomes. We hypothesized that teacher participation in an SE curriculum might positively impact teachers' own ratings of the SE competencies. However, results suggest that HATC and BAU teachers rated themselves similarly with an average score of about four out of five across competencies. We observed differences between HATC and BAU teachers on their ratings of teacher wellbeing (as measured by the Maslach Burnout Inventory for Educators) with BAU teachers reporting more slightly favorable, but not statistically different, responses. Additionally, we found no impact of HATC on teacher job satisfaction.

In exploring the impact on the classroom environment, we observed a negative impact of HATC on participating teacher's ratings of student involvement (the extent to which students are attentive and interested in class activities, participate in discussions, and do additional work on their own) and student affiliation (the friendship students feel for each other, as expressed by getting to know each other, helping each other with work, and enjoying working together). As described above, teachers reported challenges related to implementation of HATC, including student engagement and chronic absenteeism that likely influenced their responses to survey questions about their classroom environment.

We did not detect an impact of HATC on absences or disciplinary referrals, as measured by student data requested from RIMSD. Additionally, we did not detect an impact of HATC on students' academic achievement in reading or mathematics, as measured by the NWEA MAP assessment. Further, we did not observe any moderating effect of student demographics or teacher baseline variables on absences, disciplinary referrals, or achievement on these outcomes.

Notably, we observed a low correlation between teachers' ratings of students' SEL competencies and students' ratings of their own SEL competencies. Results based on student and teacher ratings (i.e., using one, or the other, or the average of both, if both are available) suggested that males in the HATC condition scored lower than females. However, when using student self-ratings only, the difference between these groups was reduced. The interaction between how SEL is rated (by self or others), gender, and treatment condition (HATC or BAU), is important to investigate further. Our preliminary results suggest that teachers and students may be rating different constructs, or different dimensions of the same construct. This will be important to consider moving forward as RIMSD determines what assessment tool best fits their needs and how data from each tool can be used to inform decision making about programming and also individual student needs.

There are two additional considerations when interpreting findings from this impact study. First, there was a very compressed program development timeline, which meant there was no time to pilot the curriculum. The year of the RCT was the first time the program was implemented. While both CWK and RIMSD administrators were very responsive to feedback from teachers and students (e.g., reducing implementation to four days per week in RIHS, and bringing in extra technical support during filming), these implementation challenges and adjustments took place during the impact study.

Second, administrators in RIHS were excited to implement a structured program during advisory period, and make productive use of that time with a curriculum that could improve student SE competencies. However, it was difficult for teachers to engage students in HATC while their peers (those not in implementing classes) were able to use their advisory period to socialize, receive academic support, or complete other work. If issues remain around the use of advisory time, teachers proposed several alternatives. Several teachers suggested that HATC could be an elective that students chose to take or perhaps students with SE needs are recommended to take. Overall, going forward RIMSD will need to identify the optimal time and space for HATC implementation to allow the program to maximally benefit students.

In response to the implementation challenges and successes noted above, RIMSD administrators and CWK worked together to adapt the HATC curriculum for the 2024–2025 school year based on the feedback provided by teachers and interim data presented from teacher surveys and interviews. At RIHS, HATC will be implemented in all ninth grade advisory classes for three days per week. As all ninth graders will be receiving the curriculum, this should eliminate the unfairness that some past students felt because they lost their advisory time when their peers did not. Implementation went schoolwide at TMLC. It will be important to continue to examine if the smaller class sizes and teacher-student relationships at TMLC continue to facilitate the successful implementation of the curriculum. The optimal classroom environment for implementation will be important to consider as project scaling continues. To further support teachers, CWK provided all participating teachers with a pacing guide aligned with a revised curriculum scope and sequence, and importantly, shifted the order of activities so students received access to the film kits and filming activities earlier in the curriculum.

Beginning in the 2024–2025 school year, RIMSD hired an instructional coach to assist with continued fidelity of implementation, coaching support, and sustainability. In future years, RIMSD intends to hire additional instructional coaches, who have demonstrated strong student and colleague relationships, and experience teaching SE learning lessons at the classroom level. RIMSD hopes to take full ownership of this curriculum and embed it within the culture of their two high schools. To achieve this goal, RIMSD intends to codify the newly developed HATC components—including manuals, videos, policy briefs, and hands-on guidance regarding leadership strategies, training, curriculum implementation—so that the curriculum continues to be implemented with clear guidance and fidelity. There will also be an implementation guidebook, developed in accordance with the HATC model and the validated program parameters from this project. These resources, as well as insights gleaned during the implementation process, will be available through an online resource center that includes blogs, how-to guides, articles, and other resources. Notably, in years four and five of the grant, RIMSD plans to invite the other districts to visit and discuss the opportunities of scaling out HATC more broadly. Overall, RIMSD intends to leverage this five-year grant into a long-term strategy for bolstering the SEL skills of high school students in Rock Island and beyond.

While HATC showed limited measurable impact during its first year, implementation insights, gender-based findings, and teacher/student feedback have informed significant improvements for future years. The Empirical Education team will continue to work with CWK and RIMSD to formatively evaluate the implementation and impact of HATC, and refine and improve the HATC curriculum, as project scaling continues. It is important that through this partnership, we continue to monitor student engagement, the impact of absenteeism, the appropriateness of data collection tools (e.g., when should student-ratings vs. teacher-ratings be used), the unique implementation strengths of teachers and students in TMLC and RIHS, and the potential to provide equitable access to SEL curriculum. Our hope is to contribute to the national conversation about SEL support and the local understanding of what works for Rock Island.