Updating Evidence According to ESSA

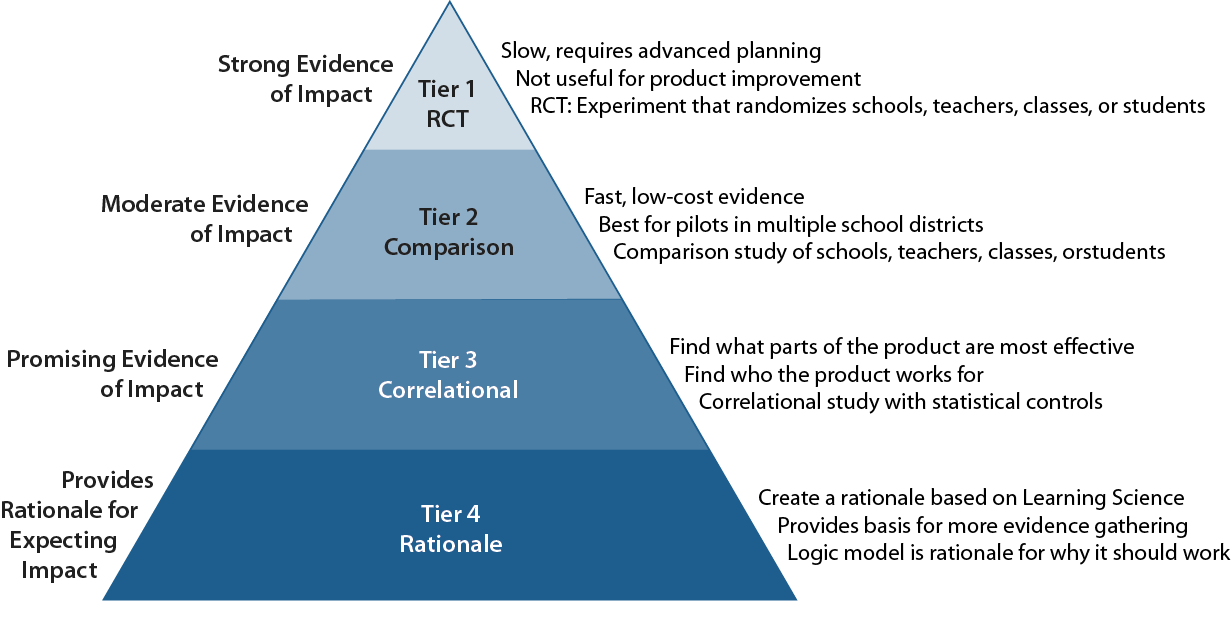

The U.S. Department of Education (ED) sets validity standards for evidence of what works in schools through The Every Student Succeeds Act (ESSA), which provides usefully defined tiers of evidence.

When we helped develop the research guidelines for the Software & Information Industry Association, we took a close look at ESSA and how it is often interpreted. Now, as research is evolving with cloud-based online tools that automatically report usage data, it is important to review the standards and to clarify both ESSA’s useful advances and how the four tiers fail to address some critical scientific concepts. These concepts are needed for states, districts, and schools to make the best use of research findings.

We will cover the following in subsequent postings on this page.

- Evidence According to ESSA: Since the founding of the Institute of Education Sciences and NCLB in 2002, the philosophy of evaluation has been focused on the perfection of one good study. We’ll discuss the cost and technical issues this kind of study raises and how it sometimes reinforces educational inequity.

- Who is Served by Measuring Average Impact: The perfect design focused on the average impact of a program across all populations of students, teachers, and schools has value. Yet, school decision makers need to also know about the performance differences between specific groups such as students who are poor or middle class, teachers with one kind of preparation or another, or schools with AP courses vs. those without. Mark Schneider, IES’s director defines the IES mission as “IES is in the business of identifying what works for whom under what conditions.” This framing is a move toward a broader focus with more relevant results.

- Differential Impact is Unbiased. According to the ESSA standards, studies must statistically control for selection bias and other sources of bias. But biases that impact the average for the population in the study don’t impact the size of the differential effect between subgroups. The interaction between the program and the population characteristic is unaffected. And that’s what the educators need to know about.

- Putting many small studies together. Instead of the One Good Study approach we see the need for multiple studies each collecting data on differential impacts for subgroups. As Andrew Coulson of Mind Research Institute put it, we have to move from the One Good Study approach and on to valuing multiple studies with enough variety to be able to account for commonalities among districts. We add that meta-analysis of interaction effects are entirely feasible.

Our team works closely with the ESSA definitions and has addressed many of these issues. Our design for an RCE for the Dynamic Learning Project shows how Tiers 2 and 3 can be combined to answer questions involving intermediate results (or mediators). If you are interested in more information on the ESSA levels of evidence, the video on this page is a recorded webinar that provides clarification.