AERA 2024 Annual Meeting

We had an inspiring trip to Philadelphia last month! The AERA conference theme was Dismantling Racial Injustice and Constructing Educational Possibilities: A Call to Action. We presented our latest research on the CREATE study, were able to spend time with our CREATE partners, and attend several captivating sessions on topics including intersectionality, QuantCrit methodology, survey development, race-focused survey research, and SEL. We came away from the conference energized and eager to apply this new learning to our current studies and for AERA 2025!

Thursday, April 11, 2024

Kimberlé Crenshaw 2024 AERA Annual Meeting Opening Plenary—Fighting Back to Move Forward: Defending the Freedom to Learn In the War Against Woke

Kimberlé Crenshaw’s opening plenary explored the relationship between our education system and our democracy, including censorship issues and what Crenshaw describes as a “violently politicized nostalgia for the past.” She brought in her own personal experience in recent years as she has witnessed terms that she coined, including “intersectionality,” being weaponized. She encouraged AERA attendees to fight against censorship in our institutions, and suggested that attendees check out the African American Policy Forum (AAPF) and the Freedom to Learn Network. To learn more, check out Intersectionality Matters!, an AAPF podcast hosted by Kimberlé Crenshaw.

Friday, April 12, 2024

Reconciling Traditional Quantitative Methods With the Imperative for Equitable, Critical, and Ethical Research

We were particularly excited to attend a panel on Reconciling Traditional Quantitative Methods With the Imperative for Equitable, Critical, and Ethical Research, as our team has been diving into the QuantCrit literature and interrogating our own quantitative methodology in our evaluations. The panelists embrace quantitative research, but emphasize that numbers are not neutral, and that the choices that quantitative researchers make in their research design are critical to conducting equitable research.

Nichole M. Garcia (Rutgers University) discussed her book project on intersectionality. Nancy López (University of New Mexico) encouraged researchers to consider additional questions about “street race” including “What race do you think that others assume what race you are” to better understand the role that the social construction of race plays in participants’ experiences. Jennifer Randall (University of Michigan) encouraged researchers to administer justice-oriented assessments, emphasizing that assessments are not objective, but rather subjective tools that reflect what we value and have historically contributed to educational inequalities. Yasmiyn Irizarry (University of Texas at Austin) encouraged researchers to do the work of citing QuantCrit literature when reporting quantitative research. (Check out #QuantCritSyllabus for resources compiled by Yasmiyn Irizarry and other QuantCrit scholars.)

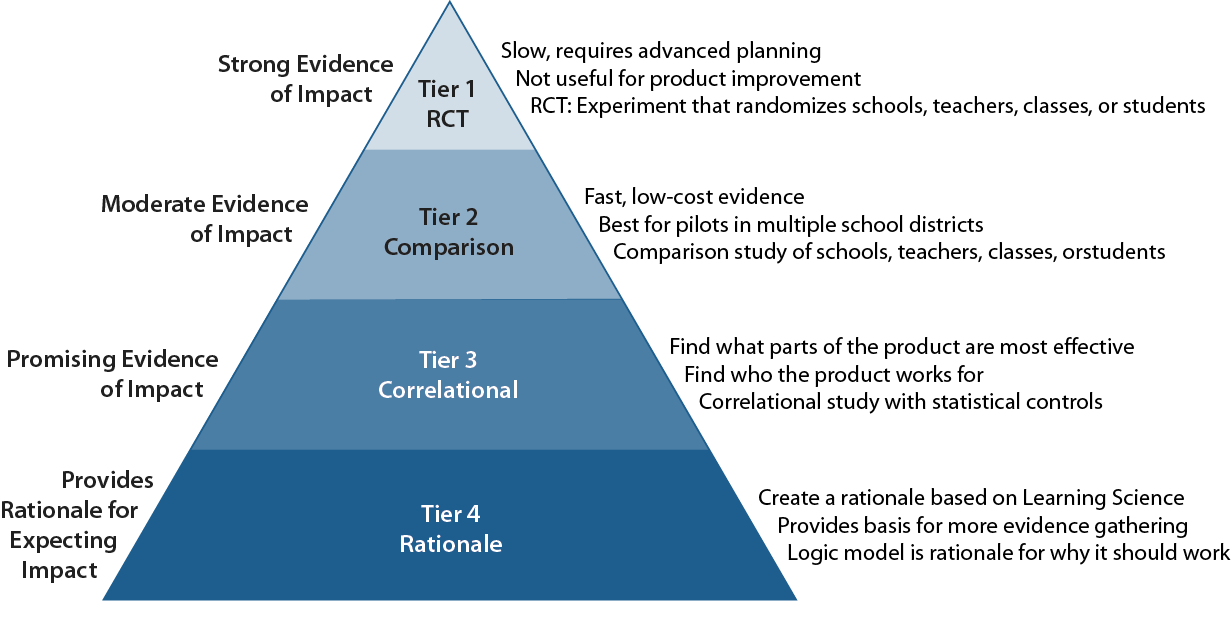

This panel gave us food for thought, and pushed us to think through our own evaluation practices. As we look forward to AERA 2025, we hope to engage in conversations with evaluators on specific questions that come up in evaluation research, such as how to put WWC standards into conversation with QuantCrit methodology.

The Impact of the CREATE Residency Program on Early Career Teachers’ Well-Being

Andrew Jaciw, Mayah Waltower, and Lindsay Maurer presented on The Impact of the CREATE Residency Program on Early Career Teachers’ Well-Being, focusing on our evaluation of the CREATE program. The CREATE Program at Georgia State University is a federally and philanthropically funded project that trains and supports educators across their career trajectory. In partnership with Atlanta Public Schools, CREATE includes a three-year residency model for prospective and early career teachers who are committed to reimagining classroom spaces for deep joy, liberation and flourishing.

CREATE has been awarded several grants from the U.S. Department of Education, in partnership with Empirical Education as the independent evaluators. The grants include those from Investing in Innovation (i3), Education Innovation and Research (EIR), and Supporting Effective Educator Development (SEED). CREATE is currently recruiting the 10th cohort of residents.

During our presentation, we looked back on promising results from CREATE’s initial program model (2015–2019), shared recent results suggesting possible explanatory links between mediators and outcomes (2021–22), and discussed CREATE evolving program model and how to identify/align more relevant measures (2022–current).

The following are questions that we continue to ponder.

- What additional considerations should we take into account when thinking about measuring the well-being of Black educators?

- Certain measures of well-being, such as the Maslach Burnout Inventory for Educators, respond to a more narrow definition of teacher well-being. Are there measures of teacher well-being that reflect the context of the school that teachers are in and/or that are more responsive to different educational contexts?

- Are there culturally-responsive measures of teacher well-being?

- How can we measure the impacts of concepts relating to racial and social justice in the current political context?

Please reach out to us if you have any resources to share!

Survey Development in Education: Using Surveys With Students and Parents

Much of what I do as a Research Assistant at Empirical Education is to support the design and development of surveys, so I was excited to have the chance to attend this session! The authors’ presentations were all incredibly informative, but there were three in particular that I found especially relevant. The first was a paper presented by Jiusheng Zhu (Beijing Normal University) that analyzed the impact of “information nudges” on students’ academic achievement. This paper demonstrated how personalized, specific information nudges about short-term impacts can encourage students to modify their behavior.

Jin Liu (University of South Carolina) presented a paper on the development and validation of an ultra-short survey scale aimed at assessing the quality of life for children with autism. Through the use of network analysis and strength centrality estimations, the scale, known as Quality of Life for Children with Autism Spectrum Disorder (QOLASD-C3), was condensed to a much shorter version that targets specific dimensions of interest. I found this topic particularly interesting, as we are always in the process of refining our survey development processes. Finding ways to boost response rates and minimize participant fatigue is crucial in ensuring the effectiveness of research efforts.

In the third paper, Jennifer Rotach and Davie Store (Kent ISD) demonstrated how demographics play a role in how students score on assessments. The authors explained how disaggregating the data is sometimes necessary to ensure that all students’ voices are heard. They explain that in many cases, school and district decisions are driven by average scores, often leading to the exclusion of those who are above or below the average. The authors explain that in some cases, disaggregating survey data by demographics (such as race, gender, or disability status) may be the most helpful in uncovering a different story than just the “average” will tell.

— Mayah

Sunday, April 14, 2024

Conducting Race-Focused Survey Research in the P-20 System during the Anti-Woke Political Revolt

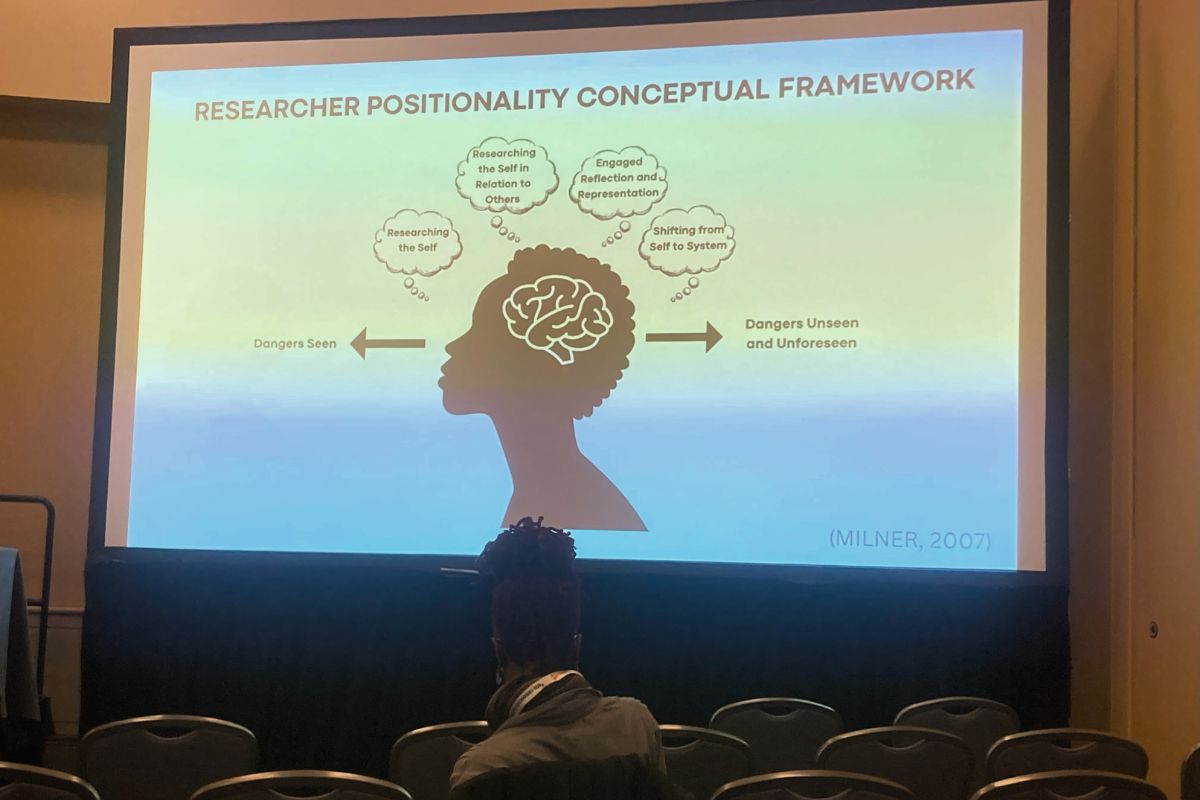

The four presentations in the symposium titled Conducting Race-Focused Survey Research in the P–20 System During the Anti-Woke Political Revolt focused on tensions, challenges, and problem-solving throughout the process of developing the Knowledge, Beliefs, and Mindsets (KBMs) about Equity in Educators and Educational Leadership Survey. On the CREATE project, where we are constantly working to improve our surveys and center racial equity in our work, we are wrestling with similar dilemmas in terms of sociopolitical context. Therefore, it was very eye-opening to hear panelists talk through their decision-making throughout the entire survey development process. The North Carolina State We-LEED research team walked through their process step-by-step, from conceptualization to the grounding literature and conceptual framing, and instrument development to cognitive interviews, and sample selection to recruitment strategies.

I particularly enjoyed hearing about cognitive interviews, where researchers asked participants to voice their inner monologue while taking the survey, so that they could understand participant feedback and be responsive to participant needs. It was also very helpful to hear the panelists reflect on their positionality and how their positionality connected to their research. I am highly anticipating reviewing this survey when it is finalized!

— Lindsay

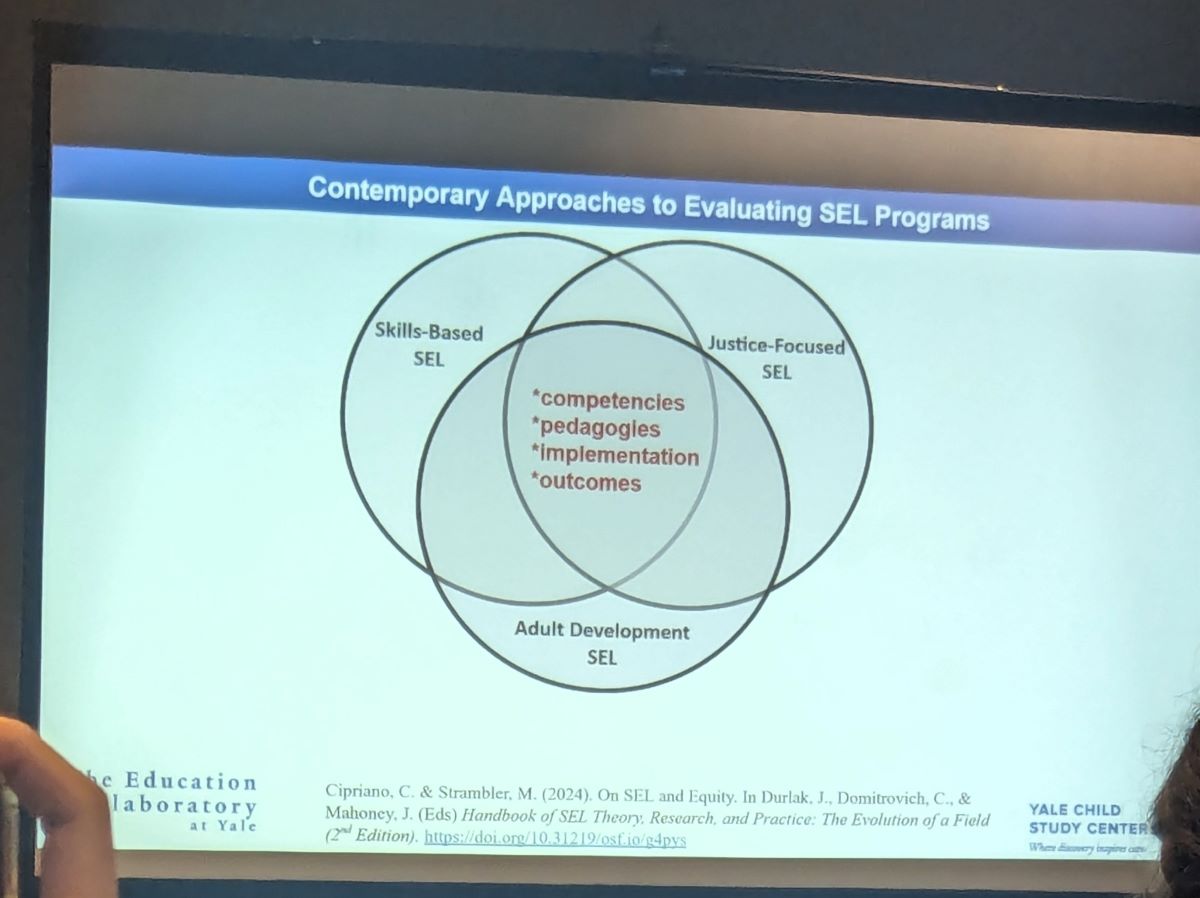

Contemporary Approaches to Evaluating Universal School-Based Social Emotional Learning Programs: Effectiveness for Whom and How?

I was excited to attend a session focused on Social Emotional Learning (SEL), a topic that directly relates to the projects I am currently involved in. The symposium featured four papers that all highlighted the importance of conducting high-quality evaluations of Universal School-Based (USB) SEL initiatives.

I was excited to attend a session focused on Social Emotional Learning (SEL), a topic that directly relates to the projects I am currently involved in. The symposium featured four papers that all highlighted the importance of conducting high-quality evaluations of Universal School-Based (USB) SEL initiatives.

In the first paper, Christina Cipriano (Yale University) presented a meta-analysis of studies focusing on SEL. This meta-analysis demonstrated that of the studies reviewed, SEL programs that were delivered by teachers showed greater improvements in SEL skills. This paper also provided evidence that programs that taught intrapersonal skills before teaching interpersonal skills showed greater effectiveness.

The second paper was presented by Melissa Lucas (Yale University) and underscored the necessity of including multilingual students in USB SEL evaluations, emphasizing the importance of considering these students when designing and implementing interventions.

Cheyeon Ha (Yale University) presented recommendations from the third paper, which underscored this point for me. The third paper was a meta-analysis of USB SEL studies in the U.S., and it showed that less than 15% of the studies it reviewed included student English Language Learner (ELL) status. Because students with different primary languages may respond to SEL interventions differently, understanding how these programs work on students based on ELL status is important and useful in better understanding an SEL program.

The final paper (presented by Christina Cipriano) provided methodological guidance, which I found particularly intriguing and thought-provoking. It highlighted the importance of utilizing mixed methods research, advocating for open data practices, and ensuring data accessibility and transparency for a wide range of stakeholders.

As we continue to work on projects aimed at implementing SEL and enhancing students’ social-emotional skills, the insights shared in this symposium will undoubtedly prove valuable in our efforts to conduct high-quality evaluations of SEL programs.

— Mayah